Katsushika Hokusai

1760-1849

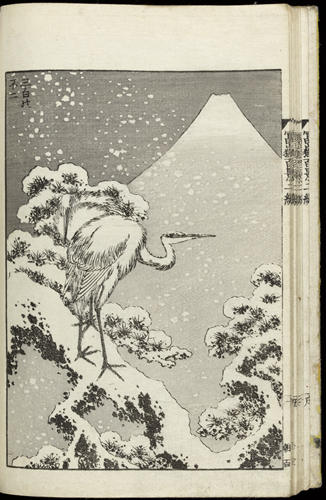

One hundred views of Mount Fuji

Fugaku hyakkei

Printed book from woodblocks, volume two of three, second edition. Publisher: Eirakuya Tôshirô (Tôhekidô) Nagoya, 1835 (date of first edition).

Given by T. H. Riches 1913

In this book Hokusai depicted Fuji from every conceivable viewpoint, and with additional ways of representing or suggesting the famous shape of the mountain conjured from his own imagination.

Fuji is a volcano 3776 metres above sea level and visible on clear days from Edo (Tokyo) sixty miles away. According to tradition it was thrown up in a massive earth upheaval in 286 BC. Regarded as the seat of the Shintô gods and dotted with temples, its significance and exceptional natural beauty attracted pilgrims, poets and artists over many centuries, and by the 1830s a Fuji-worshipping cult flourished in Edo. Fuji was often associated with snow because it was supposed to be so high that snow remained on its summit all year round.

Hokusai titled this illustration ‘Three whites Fuji’ (Sanpaku no Fuji), in reference to a set formula in Chinese-style Japanese painting, which usually combined the three white subjects: snow, white bird (heron or falcon) and white flower (plum or narcissus). Hokusai’s conceit in this image was to replace the flower with Fuji, which was always white on top.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Utagawa Kuniyoshi

1797-1861

Black hood

Kuro zukin

Colour print from woodblocks with blind embossing (karazuri) and metallic pigment. Shikishiban format surimono. Printer: Keiindô Shinzô. Poets: Sekaitei Kamendo, Hanamitei Tokiwa. c.1829.

Given by E. Evelyn Barron 1937

From the series ‘Elegant women’s Water Margin - 108 sheets’ (Fûzoku onna Suikoden hyakuhachi-ban no uchi) commissioned by the Hisakataya poetry group. In each print a woman from contemporary life is depicted with a clever allusion to one of the heroes of the Water Margin (Suikoden), a story of the legendary exploits of a group of Chinese brigands during the Northern Song dynasty (1101-26), which had been the subject of Kuniyoshi’s hugely successful first set of warrior prints around 1827.

A courtesan in winter overkimono and high clogs (geta) is seen on the bank of the Sumida River. Courtesans always had bare feet rather than wearing the split-toed socks (tabi) worn by other women.

The image parodies the Water Margin tale of exiled arms instructor Hyôshitô Rinchû (‘Panther Head’), who can be seen killing his would-be assassin in the tall print by Yoshitoshi displayed in the wall case in front of you. Possible allusions to that incident include the snowy setting and the distant plume of smoke (possibly from a tile kiln), while the folded plain umbrella (bangasa) may be intended to echo Rinchû’s sword, and the black winter hood may mimic his characteristic black hair and beard.

Takehara Shunchôsai

active 1772-1801

Illustrated famous places in Yamato

Yamato meisho zue

Printed book from woodblocks. Author: Akisato Ritô Meshimori. Publisher: Takehashi Heisuke (Shonoya). Osaka, 1791.

Given by T. H. Riches 1913

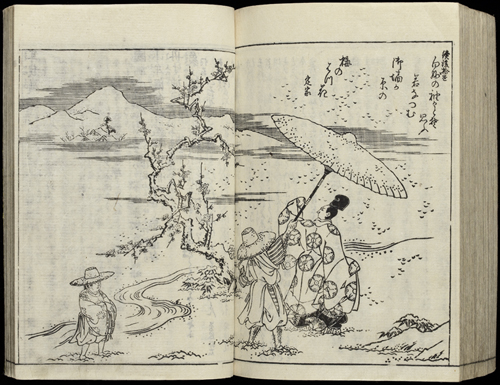

An illustrated gazetteer to the province of Yamato (modern Nara Prefecture). The illustration by Shunchôsai on this page features a poem (waka) by Fujiwara Teika (1162-1241):

> I almost took them

for white sleeves, those branches

of first plum blossoms

at Mikakigahara

where they are picking young greens.

(translation: Alfred Haft)

Mikakigahara may be an area of Yoshino, or it may refer to the fields beyond the walls of a palace garden.

The illustration shows a courtier (perhaps the poet) walking through falling snow while admiring blossom. As so often in poetry, snow and blossom are almost interchangeable, visually and metaphorically. His attendant shelters him with the curved ‘clipped fingernail’ umbrella (tsumaore) reserved for nobles.

Kuniyoshi stole all the figures from Shunchôsai’s design when he designed a print illustrating a poem by Emperor Kôkô (830-887) for the series ‘One hundred poets: one poem each’ (Hyakunin isshu no uchi), c.1842.

Kôkô composed his poem while still a prince, to accompany a gift of young greens, which were customarily gathered and eaten at New Year.

For my lord’s sake

I went out into the fields of spring

to pick young greens

while on my robe

the snow kept falling and falling.

– Emperor Kôkô

(translation: Joshua S. Mostow)

The commentary printed in the cartouche on Kuniyoshi’s print explains that the young greens provide protection from all kinds of malady.

P.3692-R

Totoya Hokkei

1780-1850

Hôjô Tokiyori

Colour print from woodblocks with blind embossing (karazuri) and metallic pigment. Shikishiban format surimono. Poets: Yôkyûtei Kazutaka, Eijudô Kanenobu, Hinanoya Haruko. 1834.

Given by E. Evelyn Barron 1937

In the Nô play Hachinoki (The Potted Trees), Shogun Hôjô Tokiyori (1227-1263) is travelling incognito as an itinerant priest when a heavy snowfall forces him to seek shelter in the house of Tsuneyo Genzaemon, an impoverished warrior living in the remote village of Sano (in present-day Gunma). Tsuneyo explains that he was forced from the service of Shogun Tokiyori when his land was stolen. He sacrifices his three treasured bonsai trees to make a fire for his guest. On returning to Edo, Tokiyori summons his old retainers to battle, and when Tsuneyo arrives in worn armour and riding his emaciated horse, Tokiyori restores his land and gives him three extra estates, named Plum, Cherry and Pine after the trees that he sacrificed.

In this New Year print for the year of the horse, it seems to be Tsuneyo’s wife who chops down the trees. The first ‘crazy verse’ (kyôka) recalls the saying ‘a heavy snowfall foretells a bountiful year’:

> A heavy snow

foretells the coming bounty

of three landed estates,

to be awarded as tribute

at the start of a horse year.

– Yôkyûtei Kazutaka

Untethered

from branches

about to be cut for kindling,

the spring colts at Sano

race together in the snow.

– Eijudô Kanenobu

The spear-plum stands alone

in the chilly falling snow,

but its blossoms

seize a chance to perfume the air,

giving a fine start to the year.

– Hinanoya Haruko

(translations: Alfred Haft)

Totoya Hokkei

1780-1850

Plum and painted shell

Colour print from woodblocks with blind embossing (karazuri) and metallic pigment. Shikishiban format surimono. Poets: Shinbuntei Nagatake, Kisaro Kiyonori. c.1830-4.

Given by E. Evelyn Barron 1937

From the series entitled ‘Essays in idleness’ (Tsurezuregusa) commissioned by the Manji poetry circle. The inscriptions include a quotation from chapter 171 of Tsurezuregusa, a prose miscellany written by Yoshida Kenkô in 1324-1331:

> ’It happened once that a man playing the game of shell-matching took no notice of the shells before him, he was so busy looking to the side…’

Shell-matching involved pairing or reuniting poems or images painted inside the separated halves of shells. The scene in this shell is from the famous eleventh-century novel, The Tale of Genji, by Murasaki Shikibu. Prince Niou has fallen in love with Ukifune (‘drifting boat’), mistress of his friend Kaoru. Disguised as Kaoru, Niou braves a journey through deep snow, reaching Ukifune at night. In this scene he takes her by boat to a house across the Uji River, with the moon in the dawn sky. Afterwards they exchange poems:

Niou:

Snow upon the hills, ice along frozen rivers:

these for you I trod, yet for all that never lost

the way to be lost in you.

Ukifune:

Quicker than the snow, swirling down at last

to lie by the frozen stream, I think I shall

melt away while aloft yet in mid-sky.

(translation: Royall Tyler)