Utagawa Hiroshige

1797-1858

Mount Yuga in Bizen Province

Bizen Yugasan

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format. Publisher: Yamadaya Shôjirô (Kinkyôdô). 08/1858.

Given by T. H. Riches 1913

From the series ‘Sumo bouts between landscapes and seascapes’ (Sankai mitate sumô) published by Kinkyôdô in 1858. The title is inscribed on a cartouche in the shape of the fan used by the referee at a sumo wrestling match. The series was originally intended to include 140 prints in 70 pairs, each pair comprising a landscape and seascape from one of the 70 provinces of Japan, but only ten pairs were completed. This view of Mount Yuga in Bizen Province (now in southeast Okayama prefecture) was paired with a (non-snowy) view of the sea at Tanokuchi, a village on the coast of the Inland Sea at the foot of Mount Yuga.

Mount Yuga was a major pilgrimage destination. The complex included a Shintô shrine and the Buddhist Rendai-ji monastery. The sacred harbour gate (torii) to the sanctuary appears in the companion print, Tanokuchi in Bizen Province (Bizen Tanokuchi), while further gates up the hill are seen in this print.

Utagawa Hiroshige II

1826-1869

Kintai bridge - Suo Province

Suo iwakuni Kintaibashi

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format. Publisher: Sakanaya Eikichi (Uoei). 11/1859.

Given by T. H. Riches 1913

From the series ‘One hundred views of famous places in the Provinces’ (Shokoku meisho hyakkei) published by Uoei in 1859-61.

Hiroshige II first signed himself Shigenobu but took the name of his adopted father and teacher, the more famous Hiroshige, after the latter’s death in 1858. This print may have been based on a similar view of the bridge in his master’s series ‘Pictures of famous places in the sixty-odd Provinces’ (Rokujû yoshû meisho zue) of 1853-6. Hokusai had also depicted the bridge in his series ‘Remarkable views of bridges in all provinces’ (Shokoku meikyô kiran) published around 1834.

The name of the bridge means literally ‘the bridge of the brocade sash’. Built in 1673 over the Nishiki river at Iwakuni in the province of Suo (now in Yamaguchi prefecture), it was inspired by pictures of the stone bridges over the West Lake in China. It attracted many sightseers, as well as artists.

Neither Hokusai’s nor the elder Hiroshige’s views had been snow scenes, and it is the element of snow, and the artist’s concentration on the way it lends forms an abstract force, rather than bothering too much about topographical detail, that makes this one of the younger Hiroshige’s best designs.

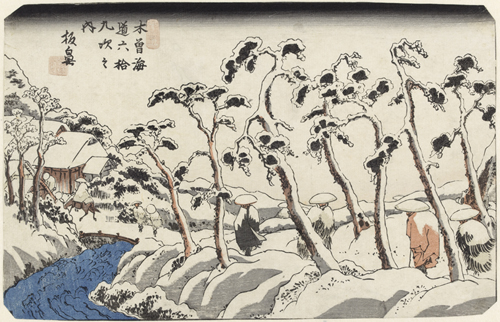

Keisai Eisen

1790-1848

Itahana

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format (trimmed). Publisher: Iseya Rihei (Kinjudô). c.1835-6.

Bequeathed by Edith Marjorie Maitland 1962

No. 15 from the series ‘Sixty-nine stations of the Kisokaidô’ (Kisokaidô rokujûkyutsugi no uchi), first published by Hôeidô and Kinjudô, c.1835-42. Takenouchi Mayohachi’s firm Hôeidô commissioned the series around 1835 from Eisen, who designed 24 prints before leaving the project, to be replaced by Hiroshige. This is one of two prints in Eisen’s style but without any signature, and the format of the inscriptions suggests that Hiroshige added these elements. Takenouchi ran into financial difficulties and brought in another publisher, Iseya Rihei (Kinjudô), who soon gained sole control.

The Kisokaidô was the second most important road in Japan (after the Tôkaidô), linking Edo, the government centre, with the old imperial capital, Kyoto, via the rugged central mountain range and the Kiso valley. Itahana was one of the 69 post stations where travellers broke their journey. Judging by the snow on the shoulders of their heavy cloaks and straw capes (mino), the approaching travellers have walked through a heavy storm.

In earlier printings, there is additional shading and a pink glow on the horizon of a lightening sky. The cold seems more intense and unremitting in this version.

Utagawa Hiroshige

1797-1858

Wada

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format. Publisher: Iseya Rihei (Kinjudô). c.1836-8.

Given by T. H. Riches 1913

No. 29 from the series ‘Sixty-nine stations of the Kisokaidô’ (Kisoji rokujûkyutsugi no uchi), first published by Hôeidô and Kinjudô, c.1835-42. Takenouchi Mayohachi’s firm Hôeidô commissioned the series around 1835 from Keisai Eisen, who designed 24 prints before leaving the project, to be replaced by Hiroshige. Takenouchi ran into financial difficulties and brought in another publisher, Iseya Rihei (Kinjudô), who soon gained sole control.

It is likely that Eisen and Hiroshige relied to a considerable extent on guidebooks and imagination when composing their views of the Kisokaidô, as there is no evidence that they made the trip along the road themselves in the 1830s.

Wada was the highest post station on the road, located at an elevation of 820 metres above sea level at the entrance to Wada Pass, which at 1650 metres formed one of the most dangerous parts of the journey, especially in the bleak winter conditions depicted here by Hiroshige. Because the next post station, Shimosuwa, was over 12 miles away, Wada flourished as an overnight stop, with over 150 buildings to accommodate all of the travellers and their pack animals.

Utagawa Hiroshige

1797-1858

Mountain and river on the Kiso road

Kisoji no sansen

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format triptych. Publisher: Okazawaya Taheiji (Shôeidô). 08/1857.

Given by The Friends of the Fitzwilliam Museum with the aid of a contribution from the Art Fund 1993

The ‘snow’ subject from the set of three landscape triptychs on the traditional theme of ‘snow, moon and flowers’ (setsugetsuka) published by Shôeidô in 1857. The linking of these elements as ‘the three friends of the poet’ came from a sentiment expressed by the Chinese poet Bai Juyi (772-846), who was influential in Japan. The theme recurs in classical Japanese literature. The three words were sometimes also used in place of numerals to number sequences, or to indicate seasons: snow/winter, moon/autumn, flowers/spring. Together with birds/summer they made up the four seasonal elements (kachô gessetsu).

This print shows the Kisokaidô - the mountain road between Edo and Kyoto that had been the subject of an earlier print series completed by Hiroshige in 1842 (displayed in the two prints above this).

The abstract quality of the design recalls Chinese painting styles. As in Hiroshige’s late landscape paintings, the human figure is virtually absent, and where we can spot one it is dwarfed by the vast scale of the landscape, which is emphasized by the snow.

Utagawa Hiroshige

1797-1858

Kanbara – night snow

Kanbara – yoru no yuki

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format. Publisher: Takenouchi Magohachi (Hoeidô). c.1833.

Bequeathed by Oscar C. Raphael 1941 (received 1946)

No. 16 from the series ‘Fifty-three stations on the Eastern coast road’ (Tôkaidô gojûsan tsugi no uchi) published by Hoeidô and Senkakudô around 1833.

Hiroshige reputedly made the journey himself along the Tôkaidô from Edo to Kyoto around the eighth month of 1832, as part of the Shôgun’s annual procession to present a horse to the Imperial Court. But when he came to design his prints he often relied on guidebook illustrations for topographical detail, and used his imagination to transform his models (or his memories of autumn scenery) into winter scenes like this.

This much admired depiction of snowflakes falling on houses and hills already shrouded in a thick blanket of snow bears little relationship to Kanbara, where it rarely snows, and certainly not when Hiroshige supposedly made his trip. The landscape is bleached of colour by the snow and the darkening sky, as a few late travellers make their final steps to the village, lit only by the remaining light reflected off the snow.

An earlier printing has the sky shaded dark at the top instead of at the horizon, and additional grey shading on the roofs and in front of the houses.

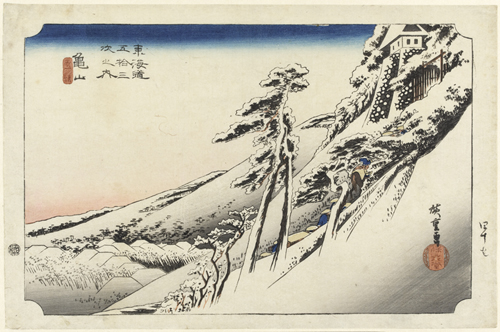

Utagawa Hiroshige

1797-1858

Kameyama – clear weather after snow

Kameyama – yukibare

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format. Publisher: Takenouchi Magohachi (Hoeidô). c.1833.

Bequeathed by Oscar C. Raphael 1941 (received 1946)

No. 47 from the series ‘Fifty-three stations on the Eastern coast road’ (Tôkaidô gojûsan tsugi no uchi) published by Hoeidô and Senkakudô around 1833.

This was the first and most famous of Hiroshige’s many series depicting the Tôkaidô, the main coastal route linking Edo, the government centre, with the old imperial capital, Kyoto. The journey of 300 miles took two weeks, with travellers resting overnight at 53 post stations designated by the first Shôgun of the Tokugawa regime in 1601. Thousands travelled the road each year: pilgrims, entertainers, messengers, traders, and large retinues serving the processions of feudal lords (daimyô). Daimyô had to travel to comply with a system of ‘alternate attendance’ that meant spending alternate years in Edo and their regional domain, with their families left hostage in Edo. Processions were serviced by a multitude of tea-shop owners, inn-keepers, palanquin-bearers and porters.

Here a daimyô’s procession can be seen climbing up towards the sixteenth-century castle above the town of Kameyama, but the figures barely register in a landscape that presages the natural grandeur and abstract power evoked in Hiroshige’s later works. This is one of the coldest and bleakest scenes in the series.

Utagawa Hiroshige

1797-1858

Fukugawa Susaki and Jûmantsubo

Fukugawa Susaki Jûmantsubo

Colour print from woodblocks, with mica flakes (kirazuri). Ôban format. Publisher: Sakanaya Eikichi (Uoei). 05/1857.

Purchased 1908

No. 107 from the series ‘One hundred famous views of Edo’ (Meisho Edo hyakkei), published by Uoei in 1856-8. The set ran to 119 prints (several designed by Hiroshige II) and was divided into seasonal sections. This was one of the snow scenes in the winter section.

An eagle prepares to dive for prey over Jûmantsubo marshes, reclaimed in 1723-6 and extending north-east from Edo Bay towards the twin peaks of snow-capped Mount Tsukuba. The viewpoint is from above Fukugawa Susaki - a narrow spit of land along Edo Bay. The vertical poles of the Fukagawa timber yards are visible on the left.

In the spring this area offered excellent shellfish gathering – perhaps hinted at in the floating bucket, one of the few signs of human activity in a desolate wintry expanse. This flat wetland was not natural habitat for the golden eagle, and it is possible that its presence is religious as well as hugely effective pictorially. The eagle was worshipped as a deity in winter at Washi Daimyôjin (‘Eagle Deity’) shrine.

An alternative, probably earlier, printing has the title cartouche in green and yellow, the eagle’s talons burnished until glossy, and flakes of mica (kira) scattered extensively to make the feathers glitter.

Utagawa Hiroshige

1797-1858

Evening snow on Hira mountains

Hira bosetsu

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format. Publisher: Yamamotoya Heikichi (Eikyûdô). c.1834.

Given by the Friends of the Fitzwilliam Museum 1941

From the series ‘Eight views in Ômi’ (Ômi hakkei no uchi) published by Eikyûdô and Hoeidô c.1834.

The classic set of eight views of Ômi Province, north-east of Kyoto, derived from the Chinese series ‘Eight views on the Xiao and Xiang Rivers’. Each view had an associated mood or time of day, and a poem. Print designers usually substituted other Japanese settings for the Ômi locations, and this was the first set of Ômi views in this newly-popular landscape format. The set was advertised as being produced ‘in muted colours in the style of the old monochromes’, intended to recall Chinese-style ink paintings.

Sets of eight always included a scene of snow that had lingered until evening, and in Ômi sets this scene was always located in the Hira mountains at the west end of Lake Biwa. These mountains were notorious for their harsh winters and heavy snow.

The ‘crazy verse’ (kyôka) in the square cartouche is based on the traditional verse for the ‘evening snow’ view by Konoe Nobutada (1565-1614):

After snowfall

the peaks of Hira at dusk

surpass the beauty of cherry blossom.