Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

1839-1892

Gentoku visits Kômei in the snow

Gentoku fûsetsu ni Kômei o tou

Colour print from woodblocks, with mica flakes (kirazuri) and gloss black (tsuyazumi). Ôban format triptych. Block-cutter: Horikô Muneoka. Publisher: Komiyama Shôbei (Musashiya). 1883.

Purchased from the Rylands Fund with a contribution from the Art Fund 2003

From the series ‘Illustrations for Romance of the three kingdoms’ (Sangokushi zue no uchi). The fifteenth-century Chinese novel Romance of the three kingdoms (Sanguo yanyi) tells of the founding of the three kingdoms of Shu, Wei and Wu after the fall of the Han dynasty in 220 AD. It became popular in Japan in the Edo period and remains so today.

Gentoku is the Japanese name for Liu Bei, who became Emperor of Shu in 221. In 207-208 he braved an arduous journey through snow and ice with his brothers-in-arms Guan Yu and Shang Fei - ‘the three heroes of Shu’ - to offer Taoist scholar Zhuge Liang, known in Japan as Kômei, a post as his key adviser. It was during a snowstorm at night when they reached Kômei’s straw hut in the mountains, where he was living as a hermit. He was initially reluctant to accept, but on their third visit he was finally moved by the sincerity of Gentoku’s tearful plea: ‘If you will not accept, Master, what will become of the people?’

Kômei is seen on the right poring over learned texts: in the absence of lamps, diligent scholars in ancient China were supposed to have read by the light of fireflies or by the reflected luminescence of snow, which they brought in from outside.

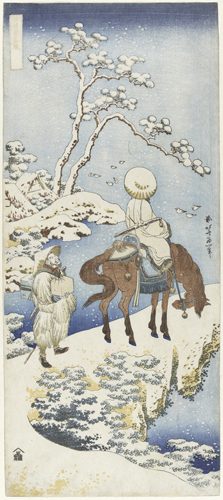

Katsushika Hokusai

1760-1849

Poet travelling in the snow

Colour print from woodblocks. Naga-ôban format. Published by Moriya Jihei (Moriji). c.1833.

Purchased from the Rylands Fund 1997

From the series of ten views, ‘True mirror of Chinese and Japanese verse’ (Shika shashin kagami), each depicting a famous Chinese or Japanese poet. Unlike other prints in the series, the poet here is not named, leading to confusion about the identity of the rider. Links between this series and Hokusai’s illustrations to two volumes of Chinese Tang dynasty poems, published in 1833 and 1836, have led to suggestions that the poet here may be Du Fu (712-70) or Han Yu (768-824), but the traditional identification with the Song dynasty poet and statesman Su Shi (1037-1101), known in Japan as Toba, seems equally convincing.

Su Shi held various government posts before being banished to the island of Hainan. As governor of Hangzhou he created a causeway across the scenic West Lake, which still bears his name. He also built a studio called Snow Hall, which he lined with snow paintings. He was admired for his snow poems, several of which might be echoed in this image: the sense of a cold pilgrimage or journey into exile, the precipitous rocks round a lake dotted with water birds, with its waters merging seamlessly into sky.

The poet’s servant wears a straw cape (mino) for the snow.

Katsushika Hokusai

1760-1849

Minamoto no Muneyuki Ason

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format. Publisher: Nishimuraya Yohachi (Eijudô). c.1835.

Given by T. H. Riches 1913

No. 28 in Hokusai’s final series of prints, ‘One hundred poems by one hundred poets explained by a nurse’ (Hyakunin isshu uba ga etoki), begun in his seventy-sixth year. The first five prints in the series were published by Nishimuraya Yohachi, and another twenty or so by Iseya Sanjirô around 1835-6 after Nishimuraya’s bankruptcy. The series was never completed, but Hokusai’s preparatory drawings for sixty or so subjects are known. The poems come from probably the most popular classical anthology, compiled in 1235 by Fujiwara no Teika, Hyakunin isshu (‘one hundred poets, one poem each’).

The figures in this print are probably hunters. The warmth of their temporary blaze contrasts with the hut on the right, abandoned to the snow. The poem by Minamoto no Muneyuki (died 939) emphasises the sadness of winter, perhaps in response to the conventional idea that autumn is the saddest season:

In the mountain village,

it is in winter that my loneliness

increases most,

when I think how both have withered -

the grasses and people’s visits.

(translation: Joshua S. Mostow)

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

1839-1892

Hyôshito Rinchû kills officer Riku near the Mountain Spirit Temple

Hyôshito Rinchû sanshinbyô no mae ni oito riku gukô o korosu

Colour print from woodblocks, with burnishing (shômenzuri) and spattered white pigment. Ôban diptych. Publisher: Matsui Eikichi (Kakuhakudô). 1886.

Purchased from the Rylands Fund with a contribution from the Art Fund 2003

This subject is from the Chinese novel, Water Margin (Shuihu zhuan, known in Japanese as Suikoden), which tells of the legendary exploits of a group of Chinese brigands during the Northern Song dynasty (1101-26). It was retold in a popular Japanese novel illustrated by Hokusai, and was the subject of Kuniyoshi’s first set of warrior prints in 1827.

Hyôshitô Rinchû had been imprisoned by the minister of war, but his sentence was commuted to service as a guard at a remote army camp. Still desiring his death, the minister sent one of his officers, Riku, to arrange Rinchû’s murder, with the stipulation that he make it look like an accident. Riku set fire to Rinchû’s guardhouse (the fire is seen in the distance), but Rinchû was at that time sheltering from the cold in a nearby temple. He was therefore able to surprise his intended assassin and kill him, and this print shows the aftermath.

The atmosphere of the snowy landscape is heightened by the use of white pigment spattered onto the surface of the print, evoking falling flakes of snow.

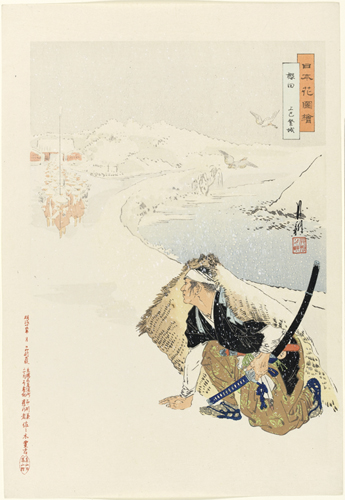

Ogata Gekko

1859-1920

Sakurada Gate – approaching the castle, third day of the third month

Sakurada – Joshi tojo

Colour print from woodblocks, with blind embossing (karazuri), gloss black (tsuyazumi) and spattered white pigment. Ôban format triptych. Publisher: Sasaki Toyokichi (Sasakiya). 1896.

Bequeathed by Henry Scipio Reitlinger 1950, received 1991

From the series ‘Pictures of flowers of Japan’ (Nippon hana zue). The ‘flower’ in this picture is implied by the name of the Sakurada (‘cherry-tree’) gate to Edo Castle. The series includes various historic figures and events. It was issued from 1892 until the end of the century by at least three publishers.

An assassin waits for Ii Naosuke and his procession, which approaches Edo Castle from the Sakurada Gate. Ii Naosuke was chief advisor to the Shôgun and a proponent of opening Japan to the west. He had signed the Harris Treaty with the United States in 1858, for which he was much criticised.

He was assassinated on a snowy morning in the third month of 1860, by a group of 17 samurai retainers from Mito, accompanied by Arimura Jisaemon, a samurai from Satsuma. Arimura cut Ii Naosuke’s neck and then committed ritual suicide (seppuku). The assassination is generally described as taking place outside Sakurada gate, but Gekko seems to have set the incident within the grounds of Edo castle, with the main moat to the right. The assassin crouches within the shelter of a straw cape (mino), while snow falls heavily. Some of the snowflakes are depicted by flicking white pigment over the printed surface.

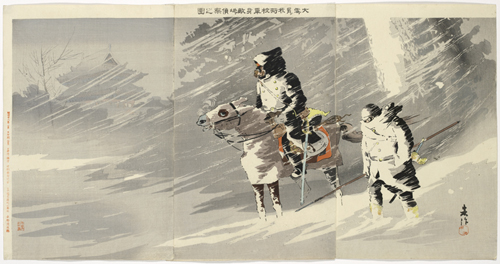

Taguchi Beisaku

1864-1903

Braving heavy snow – a Japanese officer scouts enemy territory

Taisetsu o okashite waga-shôkô tanshin tekichi o teisatsu no zu

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format triptych. Block-cutter: Watanabe Yatarô. Printer: Nakajima. Publisher: Mizuno Asajirô. 01/1895.

Bought from the Rylands Fund 2010

Besaku was one of the most gifted artists to design triptychs recording events of the Sino-Japanese war of 1894-5. At a basic level these provided the latest illustrated reportage from the front, with ten prints published each day, but in the best examples artists created imaginative works with novel graphic effects conveying atmosphere as well as immediacy.

The Japanese Second Army landed from troopships at Rongcheng Bay on the Shandong Peninsular in China between 20 and 25 January 1895, before braving the march through severe conditions to decisive battles at Weihaiwei, which fell to the Japanese on 2 February.

The severe conditions of cold, snow and ice that the troops encountered were mentioned in dispatches. Officers were sent on ahead to scout but often failed or were delayed due to the blowing winds and snow. Second Artillery Lieutenant Nanbu Kijirô recalled:

‘As far as one could see, snow covered the Shandong Peninsula. It was biting cold. Beards hung like icicles, frozen from the chin. To combat frostbite, all extremities had wool protective covers. But the cold iced even our bone marrow. The horses were too cold to continue…’