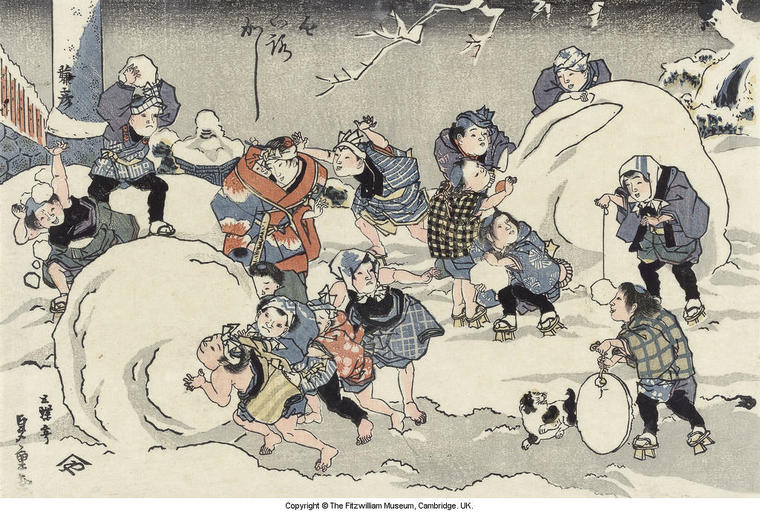

Utagawa Kuniteru

active c.1830-70

Rolling a snowball

Yukikorogashi

Colour print from woodblocks. Aiban format. Publisher: Fujiokaya Hikotarô (Shôgendô). c.1840.

Given by Matthew Rutenberg and Anne V. Lauder through Cambridge in America 2012

Kuniteru signed this print with his earlier artist’s name, Gochôtei Sadashige (he only used the name Kuniteru after his teacher Kunisada’s death in 1844).

The children in the far right background are putting the finishing touches to a giant snow rabbit (yuki usagi), whilst others are rolling a large snowball or carrying suspended pieces of ice, which they strike like the drums carried at festivals or at the opening of sumo wrestling tournaments. These were all favourite snowy pastimes for children that were effectively exploited by print designers in the late Edo period.

The game of rolling snowballs went back at least to the Heian period when it was one of the few outdoor pastimes available to women. In her Pillow book (Makura no sôshi) of c.1005, Sei Shônagon tells how she and other ladies-in-waiting to the Empress built a huge ‘snow mountain’ in the garden of her palace, and soon everyone was copying them.

Children in Japan no longer make snow rabbits (the equivalent of snowmen), but they build snow figures of Daruma (Bodhidharma) - father of the Zen sect of Buddhism that spread from India to China and Japan.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi

1797-1861

Binshiken

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format. Publisher: Wakasaya Yoichi. c.1843.

Bequeathed by Henry Scipio Reitlinger 1950, received 1991

From the series ‘Twenty-four paragons of filial piety for children’ (Nijûshi-kô dôji kagami) published by Wakasaya Yoichi, c.1843. This was based on Chinese stories of children whose self-sacrificing behaviour towards their parents provided exemplars of filial duty (kû), which ranked only behind feudal loyalty (chû) in Japan’s prioritisation of Confucian virtues.

Binshiken is outside sweeping snow, forced to work in the cold by his cruel stepmother, who is seen to the left spoiling her own two children. When Binshiken’s father discovers her cruelty, he angrily determines to throw her out, but Binshiken pleads that ‘it is better that one son should suffer cold than three children be left motherless’. This melts the heart of his step-mother and she is kind to him ever after.

The Nô play Snow on bamboo (Take no yuki) by Zeami (c.1363-1443) features some similar elements: a cruel stepmother forces her stepson to brush snow from bamboo in the yard, but it is so cold that he dies (his natural parents’ piety then brings him back to life).

Kuniyoshi probably based the figure group of the mother and her two children on a group symbolising Charity in a print or book imported by Dutch traders.